When I started working with computer music around 1990, the technology was quite different than what we have available today. Computers didn’t come with sound cards, there was no SuperCollider or Max/MSP, and disk space to store created sounds was extremely limited. To engage with the medium, I got my start working in the UIUC Computer Music Project, a lab which provided a home-built digital-to-audio converter (DAC), and a Music-V type language to work with called Music 4C. I authored (coded) various instruments for Music 4C and used them to create new works.

Make Something New

Some of my colleagues at the time focused their efforts on recreating existing instruments. They wanted an “accurate” string sound, or a pretty trumpet or clarinet timbre to come out of the speakers.

I never understood this.

If they wanted a pretty trumpet, clarinet, or violin, the floor below us was full of musicians proficient with those instruments practicing to get better every day. They could just ask one or more of them to play their piece.

A Yamaha TX81Z synthesizer ready to crank out the cheesy flute sounds

Given the potential of a new medium to make new sound, why try to reproduce the old? I wanted my software to make sounds I had never heard before—that nobody had ever heard before. This might sound like a tall order, but this is precisely what the world had already gotten over and over with each new instrument invented. Computer music was just another new instrument, but a flexible one that could facilitate the invention of many new instruments. It was an opportunity to break the rules of physics, not to adhere to them!

MIDI Fills The Planet With Crap

Then there were those that chose to focus their attention on MIDI synthesizers. While there were one or two needs I saw MIDI as useful for, mostly it seemed to be filling the planet with more crap. MIDI was nothing but canned sounds trying to imitate physical instruments, but failing miserably. Their reproductions lacked the timbral complexity of the original. In other words, MIDI took what was interesting about sound and destroyed it.

Eventually I focused my energies on the creation of GACSS, a software package that allowed myself and others to easily create and compose with (previously unheard of) new sounds. Over the years MIDI continued to flourish and still dominates today. However, composers have new tools such as Max/MSP that make it easy to create new sounds without any difficult programming, so now there’s really no excuse not to make your own thing.

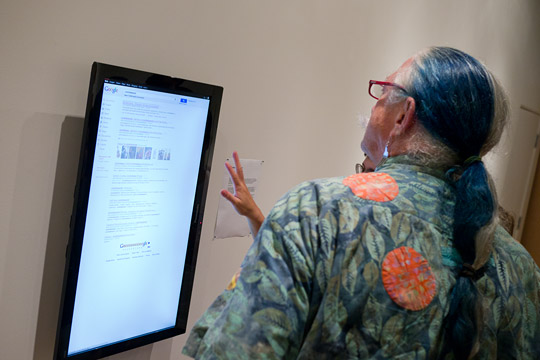

What Should a Painting Machine Make?

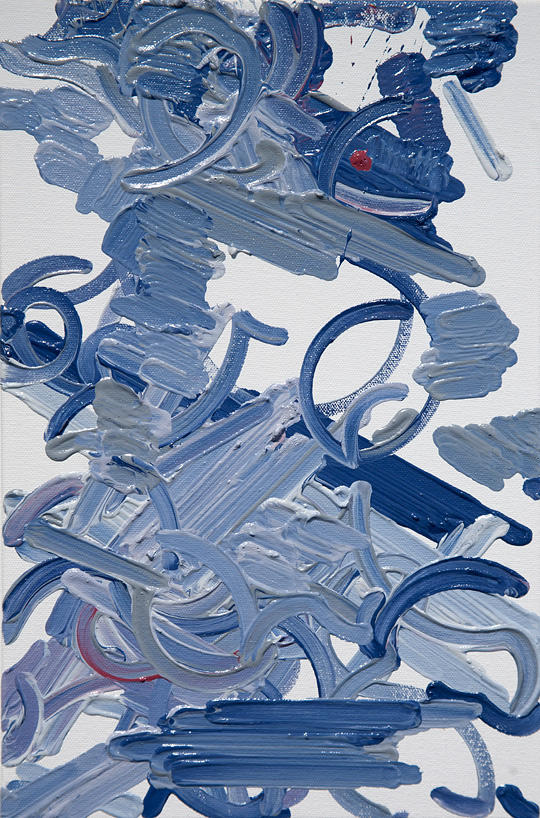

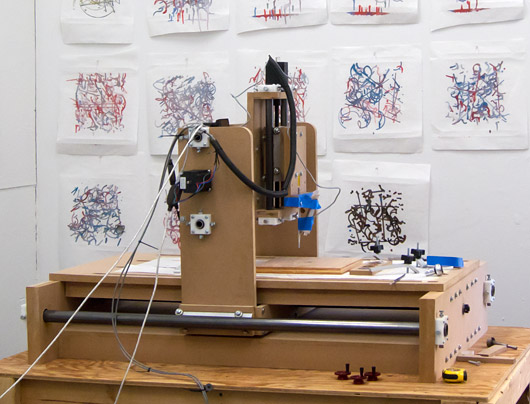

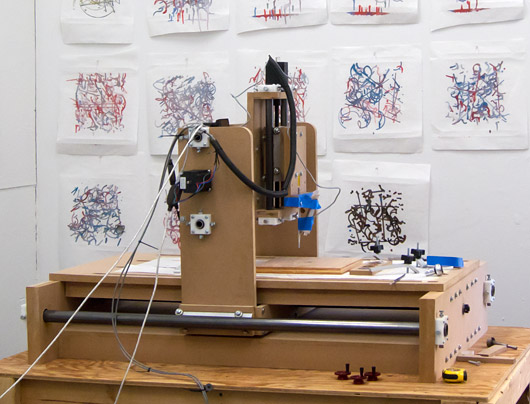

My collaborative robotic painting machine (very much still in progress). Paintings on the wall behind it are a few of its first sketches.

Fast forward to now, and one of my current projects is a collaborative robotic painting machine. This machine will develop its own body of work, accept and consider input from others, and will use that input to create both paintings and music. There are a number of painting machines out in the world that people have created. But what’s driving me nuts, twenty years after I started down this road, is that these new painting machines are typically painting paintings that already exist or that the artist can already create themselves.

Perhaps the best known painting machine is Harold Cohen’s AARON. While it’s really just software these days (no hardware component), his goal for the machine is for it to paint paintings like Harold Cohen paints paintings. It’s an interesting technical problem, but why? Harold Cohen can already paint like Harold Cohen! Unquestionably there’s an interesting element there in seeing how the computer does it differently than Harold. But I ask the same question now that I asked before: why not use the machine to create something we haven’t seen?

I want to create machines that make things I haven’t yet seen or heard. To do so, I exploit those areas where the machine excels—and the humans don’t. In the case of a painting machine, the system is a lot better with qualities like repetition, accuracy, and endurance than I am. I can use these technological advantages to my benefit, while treating those things I’m better at (such as quick pattern recognition) as system constraints. Ideally, the result will be a new creation, something that could not have existed otherwise. But no matter what, I know it won’t be something I saw or heard last month, last year, or from all of history. And that means I have something to look forward to.