I recently talked with Fernanda Ares of Roboteknia, a Mexican robotics magazine, about my work titled Interactive Robotic Painting Machine. In addition to chatting about the machine itself, we discussed the role of technology in the arts, whether robots have ‘souls,’ and where things are headed in the art/tech world.

Roboteknia, January, 2012, pp. 24-25

While Roboteknia published an English to Spanish translation of our email interview in the January 2012 issue, I am posting my original English answers below. In what follows, the questions are all Fer’s and the answers are all mine.

Interview with Roboteknia, January, 2012

Why did you decide to combine arts with technology?

I’m compelled to make art and I’m fascinated by technology. Therefore the simple answer is that I’m combining the two things I’m most passionate about into one unified endeavor so I can do them both at the same time. However, my fascination with technology goes beyond a general interest and borders closer to obsession—an obsession with how ubiquitous digital technologies are changing our experience of the world. Whenever I use these technologies I am constantly analyzing them in terms of their cultural, social, and physiological effects. These analyses lead me to questions that I transform into works of art. I use those same technologies a medium in that art in order to draw the viewer in, to give them a point of entry that has parallels with their own technological experience. Therefore the less simple answer is that my mixing of art and technology is a composed strategy that enables a broadly accessible critical examination of those things I most care about.

What are the arts’ possibilities through the technology?

Throughout history, each new artistic medium has brought new possibilities to the artists who use them. For example, oil paint was a new technology at one time, and it enabled a vivid color representation than had not been seen before. But few people carry oil paint in their pockets, while almost everyone carries at least one computer with them everywhere they go (e.g. cell phone, laptop, tablet, etc.). They anthropomorphize them, covet them, and curse them, but regardless of the feeling of the moment, they live with them all day long. This commonality of technological experience opens up new territories for artists to explore when they use those same technologies as a medium in their work.

An additional aspect of technology-based art that’s most interesting to me is its ability to enable interactions between the art and the viewer. While previous mediums encouraged thought and contemplation, technologically-interactive artworks can now also engage in an active dialog with the viewer. They can listen and respond, they can watch and change, they can feel and adjust. I use such interactions as a strategy in my work to encourage personal consideration of the questions I’m exploring.

From where did you get the idea to create a robot that can paint? What is the purpose of your project?

I have long been interested in the potential role of adaptive or artificially-intelligent systems to the task of art making. As a composer, I have developed software that writes scores and/or creates sound. But as my focus switched to visual art, and specifically into investigations of technology, I started to think about how our everyday interactions are increasingly mediated by technology. These systems, such as mobile phones, search engines, or social networking sites, are designed to anticipate and support our needs and desires while facilitating those interactions. As these systems grow in complexity, or intelligence, how does that intelligence change what passes through them? Further, how does that intelligence evolve to make its own work for its own needs?

This last question served as the launching point for my Interactive Robotic Painting Machine. Does an art-making machine of my design make work for me or for itself? How does machine vision differ from human vision, and is that difference visible in the output? Is my own consciousness reinforced by the system or does it become lost within? In other words, it this machine alive, with agency as yet another piece of the technium, or is it our own anthropomorphization of the system that makes us think about it in these ways?

What I built to consider these questions is an interactive robotic painting machine that uses artificial intelligence to paint its own body of work and to make its own decisions. While doing so, it listens to its environment and considers what it hears as input into the painting process. In the absence of someone or something else making sound in its presence, the machine, like many artists, listens to itself. But when it does hear others, it changes what it does just as we subtly (or not so subtly) are influenced by what others tell us.

What has been your biggest challenge on this project?

Scale. The project is so broad and varied in its requirements that I had to keep refocusing myself on the final result. Only so much could be planned ahead of time and so I just had to dive in and start. I began with the building and assembling of the machine’s hardware, adapting an open-source CNC design as the starting point. Then I configured the low-level computer controls of the machine’s motors. Just that much took a long time, although it was probably only half of the work. From there I had to design and realize the machine’s “brains.” This required learning a new programming language, banging my head up against mathematical problems beyond my experience, understanding and adaptation of an artificial intelligence algorithm, and more. In the end I have a many hundred pound animated being driven by three networked computers, in need of constant care and feeding from a human (me). It has been quite a ride.

Where you have shown this project?

So far, few people have seen the machine in person, but many thousands have seen it via the Internet or other media. I hope to show it live soon, and am talking with a group in Germany about showing it there.

What was the people’s reaction?

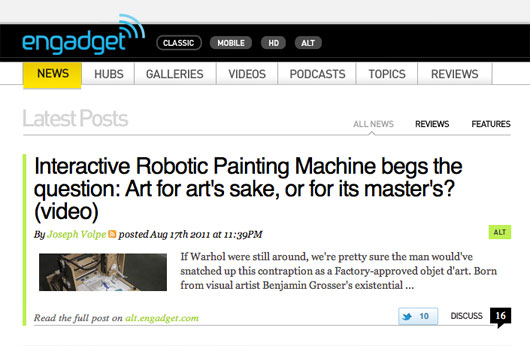

The reaction has been extensive. My videos on Vimeo.com have received more than 70,000 plays in the last few months. The machine has been written about in major online spaces, including the Huffington Post, Engadget, HackADay, Make: Blog, Salon, Discovery News, Boing Boing, and more. Lately the machine is getting more press from international sources, including sites from Taiwan, Greece, France, Russia, Brazil, Japan, Spain, Germany, Poland, and of course, Mexico. I’m humbled by the widespread response.

People’s individual reactions range from amazement to fear to admiration to near hostility. Some are worried that the machine harkens the coming a Terminator-type age of machine domination. Others, including several artists, worry that I’m going to put painters out of business. A few critique the paintings by themselves, seemingly uninterested in the machine’s role in their creation. But mostly the response has been positive and supportive. I most enjoy it when others discuss the machine in the same way that I do: as its own person, its own entity with its own feelings and goals.

When did you decide to leave the conventional arts and start getting deeper on new technologies?

It was about 3-4 years ago. I have been making art of some sort for as long as I can remember. In college I studied music composition and performance. Then I worked in the sciences, running facilities for visualization and imaging, directing and producing visualizations and animations, and writing software for remote and virtual instrument control. During that time I switched my artistic focus from music to visual, making paintings and photographs. Eventually I started to merge the two, and now making art is my full-time focus.

Who do you admire in this industry?

I am inspired by many artists and composers. Iannis Xenakis is a composer whose pioneering work combining computers and music has had a lasting effect on my aesthetic sensibility. I had the great fortune to study with Salvatore Martirano, inventor of the world’s first real-time interactive composition machine and an invaluable teacher. Within the visual arts, I admire the works of Bill Viola, Dan Graham, Roxy Paine, Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, Jim Campbell, Golan Levin, Camille Utterback, and many more.

Are there more artists doing the same as you?

There have been a number of automated or semi-automated drawing or painting machines over the years. Perhaps the most well known is Harold Cohen’s AARON, a software-based painting system that he has trained for more than 30 years to create paintings like his own. Others, such as Leonel Moura have built autonomous robots that draw or paint. Roxy Paine has a series of works that create sculptures or paintings using a specific automated process.

While many of these works have been inspirational for me, I believe that what sets my machine apart from these is my interest in creating not an autonomous robot, but a thinking AND feeling artificially-intelligent artist, one that makes its own paintings in its own style while listening for input from its audience. One that considers that input as feedback into its own artistic process, potentially modifying what it does based on what it hears. This opens up questions of agency while challenging our notions of creativity and inspiration.

What are the countries that are going ahead in arts and technology?

Berlin, Germany has become a center of activity within technology-based new media art. Europe in general appears to be quite active in this area. I’m sure other countries or regions are just as active, but few provide artists with the same levels of public institutional support as they do. Thus it may simply be that there are many pockets of activity I’m unaware of due to lack of promotion or resources to publicize the efforts. The USA certainly has a growing base of artists working with technology. Art schools across the country continue to add new media programs that support technology-based art practices. However, support for this work within US museum structures is still in its infancy.

There are plenty of other places around the globe where interesting things are happening but I wouldn’t pretend to be able to exhaustively list them.

Are you working right now on another project?

I am currently working on a piece uses protocols of interaction between two embodied computational systems to explore the role of gestural communication and how it is being changed by online social spaces. These systems, which will be represented by interactive human forms on screens, will use artificial intelligence to enable gestured communication between themselves, and between themselves and the viewer. With this work I continue to be interested in issues of agency and anthropomoprhization. What is the relationship between these systems and the viewer? Are they the subject or the object?

How are robots influencing your daily life?

Almost any product we touch these days was built or partially-built by a robot somewhere. Everything from our cars to our phones, from our furniture to our food was assembled, drilled, or packaged by a robotic system. If we expand our definition of robotics to include artificially-intelligent computational systems, then that list grows even longer. These machines and systems have long-reaching implications in terms of their political, social, cultural, and economic effects on society. If it can be automated, it will. If it can’t, it will be soon. At this point we literally cannot escape these systems because we have designed a society dependent on them.

You are teaching arts in a university. Are your students interested in this kind of project? What is the function that you perform so you can motivate them?

This year I am teaching two different courses on the topic of interaction, one that focuses on conceptual design and another that emphasizes the realization of designed interactive experience. In each course I show lots of examples from artist’s works, and we discuss readings by artists and scholars on relevant topics. Today’s undergraduates can’t recall a world without the world wide web. They can barely recall a world without cell phones. I find that because of this, at first they sometimes have trouble seeing how their own human-machine interactions are the result of composed pathways. But they also have a hunger to see it, to consider it, and to redesign them for themselves and others. As a teacher, the best thing I can do is to give them the tools to teach themselves, to show them how I learn, and to react to and critique their creations. That is all they need.

Could you consider yourself a robot developer?

I consider myself an artist, not a robotics developer. My machines are crude from an engineering perspective. My programming is crude from a software perspective. But regardless, my machine is an animated being with its own ideas and its own motivations. For me, what it makes us think about is more important than what it literally makes for us.

Where or how did you learn robotic?

I picked up all the basics from books and the Internet. I am a strong believer in the importance of free information, and so much of my art practice depends on it. I post my own how-to information on my website and various forums around the web in order to return the favor to others.

What is your answer to the people who say that a robot can not create art?

They are wrong. Look!

Do you think that in every robot, there is a creative human soul?

I’m not sure I’d use the word ‘soul’, but I understand the question. Perhaps I’d rephrase it to ask whether a robot is alive? Does it have agency? Can it make decisions for itself and not just for its designer? How does what it sees differ from what we see, and is that difference visible in what it produces? Is a designer’s consciousness reinforced by the system she builds, or does it become lost within? I won’t answer these questions for you. Instead I built my Interactive Robotic Painting Machine as a way to encourage everyone to think about them for themselves.

Where did you assemble your machine?

Since it took me over a year from start to finish, the machine was assembled in multiple locations. These include my home studio and workshop, a warehouse studio I rented, and now my studio at the university. The programming of the system was accomplished in those places, as well as in my favorite coffee shop.

How does the robotic painting machine work?

The system is built from a complex mix of hardware and software components, all networked together and managed from a central control system. This central software utilizes a genetic algorithm (GA) as its decision engine, making choices about what it paints and how it paints it. Audio captured by its shotgun microphone is subject to real-time fast Fourier analysis, providing the system with useful data about what it hears. The resulting painting gestures are transformed into codes that can be sent to the cartesian robot that manipulates a paint brush in three dimensions. These codes break down each gesture into a series of primitive moves, describing everything from how much pressure to use on a brush stroke to how to put more paint on the brush.

Three separate but networked computers manage the system. The first runs the central control software, custom written in Python. Using the GA, this software begins each painting with a random collection of individual painting gestures, and proceeds to paint them. As it paints, it listens to its environment, considering what it hears as input into the gesture it just made. These sounds, along with its own biases, are considered at the end of each generation of gestures and used to produce a new set of gestures from the old. Thus a single painting is a rendering of many generations on a single canvas that illustrate a path towards an evolutionarily desirable (i.e. most fit) result. A second computer manages the brush camera, its projection, and also performs the audio analysis, sending that data to the central machine. A third computer acts as the low-level manipulator of the robot, accepting move commands from the central system and using those to drive stepper motors that move the robot in real-time.

The robot itself was built by adapting an open source CNC design. In addition to fabricating and assembling each piece from scratch, I made significant custom modifications to the linear drive systems in order to facilitate fast rapids while maintaining repeatability. Luckily, because of the largeness of a paintbrush head, my accuracy requirements are less than a typical CNC design. This allowed me to design the drive system to be especially fast while using relatively low-cost and low-power motors.

It is important to understand that what the machine paints is not a direct mapping of what it hears. Instead, the system is making its own decisions about what it does while being influenceable by others. To understand this, I suggest you consider the machine an artist in its own right. Just as a human artist is influenced by what they hear (an influence that is sometimes easy to see and other times not so easy), the machine is influenced by what it hears. What it makes will be different in the absence of input, but it is not easy to trace how any input manifests as change.

Is technology the future of art?

New technologies will always play a role in new art. We’re still painting, still using cameras, and still drawing with charcoal. All of these were new at one point. What seems most interesting about this moment in time is our focus and fascination with technology as a subject in addition to a medium. Will that change? I wouldn’t pretend to be able to predict where art will go, but I expect our obsession with new technologies will continue unabated. As long as that is the case, artists will make art about it.